Hope for Tampa’s Homeless

Story and photos by Robin Rayne/ZUMA Press

Sprawled behind a former telecommunications warehouse in a quiet industrial section of Tampa, Florida,100 identical raised-floor tents are lined up in tidy rows in a 10-acre fenced and supervised

village that offers fresh hope for homeless men and women who previously lived on the streets.

Simply named “Tampa Hope,” the shelter is known in the homeless community as “Tent City.”

“Our mission is to take those who are chronically homeless, assess their needs, provide

them with the resources and tools they need to be able to gain an income and become self-

sufficient, and refer them to permanent housing,” explains Lou Ricardo, director of donor

relation at Catholic Charities Diocese of St. Petersburg, the non-profit organization that

operates the shelter.

Opened in 2021, the shelter is jointly funded by Catholic Charities and the City of Tampa.

Residents are provided with a tent, bed, blankets, shower and laundry facilities, portable

bathrooms and daily meals. Residents also work with case managers for access to health care

and social services. The shelter provides 24-hour supervision.

“We bring all the resources to bear in one location, partnering with agencies that provide

behavioral health care and substance abuse counseling. We connect them with the Social

Security Administration, and basically everything they need” to get their lives back. “We don’t

just feed them and send them on their way, we provide a continuity of care,” Ricardo said.

Tampa Hope emerged during the height of the Covid pandemic when businesses were shutting

down and homeless individuals had no place to use a bathroom or get a drink of water, Ricardo

said. City officials asked Catholic Charities to set up a shelter to keep those individuals safe,

based on the success of the non-profit’s Pinellas Hope Shelter in nearby Clearwater, Florida,

that opened in 2007. That shelter served as a model for Tampa Hope and became a model for

homeless shelters nation-wide. The charity was quickly able to set up 100 tents on land it

owned in Tampa, and Tampa Hope was born in a matter of weeks, he said

When it was time to expand, Tampa city officials helped the non-profit to find a more suitable

location. “The city helped get everything up and running as quickly as possible and helped fund

us for a few years as we get the word out,” Ricardo said.

“When folks see that they have a place to call their own and a roof over their head, there’s no

better felling than that, especially when you’ve been living on the streets,” Ricardo said. “We

treat everyone with dignity and respect. We help them get their lives back.”

Tampa Hope is a starting point, but it’s not a permanent home, Ricardo said. “The goal is to

provide building blocks so residents can get a fresh start and leave. As long as residents are

making progress, they can stay in the shelter. We work to help them find their own homes,” he

said.

“When we see former residents a year later and they’re working and self-sufficient and no

longer homeless, when they’re living in their own homes and doing well, they have that sense

of self-worth. It warms our hearts that we were able to help,” he said.

Tampa has one of the nation’s largest percentage of residents who are homeless, with numbers

in Hillsborough County well over 1,500 during a recent count. Statewide, the numbers of

homeless men, women and children have increased 50 percent in the past year, officials said.

Catholic Charities plans to triple Tampa Hope’s capacity in 2023 with the addition of 200 pre-

built, aluminum individual Hope Cottages that provide heat and air conditioning and electricity,

a lockable door, a bed and table, as well as smoke alarms and fire extinguishers, Ricardo said.

Tampa Hope is a starting point, but it’s not a permanent home, Ricardo said. “The goal is to

provide building blocks so residents can get a fresh start and leave. As long as residents are

making progress, they can stay in the shelter. We work to help them find their own homes,” he

said.

“When we see former residents a year later and they’re working and self-sufficient and no

longer homeless, when they’re living in their own homes and doing well, they have that sense

of self-worth. It warms our hearts that we were able to help,” he said.

Tampa has one of the nation’s largest percentage of residents who are homeless, with numbers

in Hillsborough County well over 1,500 during a recent count. Statewide, the numbers of

homeless men, women and children have increased 50 percent in the past year, officials said.

Catholic Charities plans to triple Tampa Hope’s capacity in 2023 with the addition of 200 pre-

built, aluminum individual Hope Cottages that provide heat and air conditioning and electricity,

a lockable door, a bed and table, as well as smoke alarms and fire extinguishers, Ricardo said.

Leaving ‘Him’ Behind

Story and photographs by Robin Rayne ©2023 ZUMA Press

Kai-Lynn Diamond held tight to the long-stemmed rose all graduating women received as they left the stage on the field at Paulding County High School’s football stadium, diplomas in hand.

For Kai-Lynn, the single flower was as much quiet recognition of her new gender as it was her school’s commencement tradition.

It also symbolized departing a place of pain and loneliness because she didn’t fit in with other students — and leaving her birth name and gender in the dust.

“I’m looking forward to university where I can be me – just a typical college girl, taking classes,” said Kai-Lynn — who wasn’t always Kai-Lynn.

Diagnosed as transgender two years ago, she transitioned to life as a girl at 16 when she was a sophomore. With the help of medically-supervised hormone replacement therapy, her body slowly assumed a more feminine shape, diffusing and relieving years of depression and emotional distress.

“When I realized I couldn’t go on living as a boy any longer, I called my mom, sobbing. I was thinking about suicide,” she recalled. “I tried to fight that feeling for years, but there came a day when I couldn’t take it anymore,” she said. “I had to leave ‘him’ behind. If I hadn’t been able to transition, I don’t think I’d be here now.”

For years, Kai-Lynn’s mother Crystal knew something was wrong. “She had a secret, but I had to let her tell me. She said, ‘If I can’t live as a girl I don’t want to be here anymore.’ She didn’t feel right in her body. Self-harm was a real concern. I told her, ‘It’s 2021, and you can be whoever you want to be, and I will always love and support you.’ The transition was really easy for me because once she was able to live in her authentic gender, I knew she would thrive,” she said.

“I remember she had proclaimed ‘I’m a girl’ when she was five. She played with my makeup and liked pink and girly things. She had been in hospitals numerous times for depression growing up, but neither of us even knew what the term ‘transgender’ meant until two years ago,” she said.

“Bullied and beat-up by classmates” through middle school, Kai-Lynn learned to keep to herself but sank into deep loneliness. “We were living in a redneck town, and I just didn’t fit in anywhere,” she said. “For a while, I thought I had a few friends in school, but they disappeared after I came out. I usually ate my lunch alone in a locker room to avoid the stares and whispers. It’s been very lonely ever since.”

When the stress of living in the wrong gender was lifted, the heaviness was gone, Crystal said. “I could see a real difference in her personality. She blossomed and her depression faded. She became much more talkative and engaging,” she said. “She likes the person she’s become.”

Kai-Lynn met a young college student who became a boyfriend and introduced her to skateboarding, “where people can just be themselves,” she said.

Crystal spent “tons of money” on therapy for her child before hormone treatments could begin. Insurance didn’t cover any of it. “The therapy was all out-of-pocket, but we wanted this to be the right decision,” she said. She paid for her daughter’s legal name change. Kai-Lynn’s hormone treatments, prescribed and supervised by an endocrinologist experienced in gender issues, will continue for life.

Kai-Lynn hopes to attend university after a gap year. She works in a retail clothing shop several days a week, saving her money, and looking forward to her new life. “I want to go to college, study forensic science, make more friends, and just live my life,” she said.

It is the despair of living in a gender that never fits – especially for young people who ‘know that they know’ their true selves, that Kai-Lynn wants state legislators to recognize.

She counts herself as one of the ‘lucky ones,’ having dodged a new Georgia law that would have blocked her gender transition had she been 16 years old now, and needing to begin medical intervention for gender dysphoria. “The current anti-trans political climate is getting uglier every day,” she said. “For me, transitioning when I did saved my life.”

In March, Gov. Brian Kemp signed SB140 into law which prevents residents under 18 from receiving gender-affirming medical care. The law was created by Republican-heavy legislature “to ensure we protect the health and well-being of Georgia’s children,” Kemp tweeted. In addition to restricting gender-affirming care for transgender youth under 18, penalties may be added for doctors who attempt to provide it, critics observed.

An open letter from more than 500 Georgia physicians and therapists, delivered to legislators shortly before the controversial bill was passed, asked them to “keep politics out of our clinics.” They see the law as “a clear form of government overreach that violates parents’ and providers’ rights by taking away their ability to freely discuss health care options and make decisions about what’s in the best interest of transgender youth.”

The new law is effective July 1.

Both Kai-Lynn and her mother feel intense empathy for young transgender individuals who will be forced to endure the ill-fitting body changes that come with puberty, despite their parents’ and physicians’ lobbying, support and advice.

Kai-Lynn hopes the legislators will reconsider the law before the anticipated increase in despair and self-harm within the transgender population becomes a reality. “They make these decisions that affect us without really knowing anything about us. I just think it comes from ignorance and fear,” she said.

Lisa Archibald’s ‘Gut-Wrenching Choice’

Story and photographs ©Robin Rayne/Zuma Press

Byron, GA — Lisa Archibald is reluctantly preparing her modest home for sale.

“Caring for my brother is my priority. I don’t want to move, but I won’t be able to work full time anymore if the state cuts disability budgets. We’ll need a smaller home,” she said.

Her brother is John David: 36, non-verbal, quadriplegic, and profoundly disabled because of cerebral palsy, polymicrogyria, and dysplasia. He lives in Archibald’s home and requires 24-hour care. He has seizures, restrictive lung disease and silent aspiration into his lungs, which requires constant supervision to prevent choking.

She’s been able to care for her brother in her home with the help of a patchwork of support staff, funded by a Medicaid waiver for daily in-home care. “J.D. really requires 24-7, two-to-one care, but we’ve been making do with the staffing hours we’ve had for many years,” explained Archibald, 53, who provides much of his hands-on care herself. She assumed responsibility for his care since their mother died 23 years ago. She removed walls in her living room to accommodate his bed and medical equipment. His care is center-stage in her life.

If proposed caps for support for Georgia’s medically-fragile residents become reality in two months, “Families will have to make one of the most gut-wrenching decisions of our lives: to choose between quitting our jobs, losing the ability to support ourselves and other family members in order to care for our person, or placing our medically-fragile family member in a group or nursing home,” she said.

“My brother was in a group home for several years, and nearly died. To place him back into another group home would be a death sentence. He would not survive. John David loves being at home and being a part of our community,” she said. “He knows he’s loved.”

While group homes may be a good choice for some people with developmental disabilities, those who are also medically fragile are not usually a good fit, Archibald explained. “The homes aren’t set up for the magnitude of needs this group has, and the state doesn’t have the ability to provide the needed oversite,” she said.

Archibald’s brother needs a continuity of care that can only come from long-term staff members with proper training, and group or nursing homes are too often a revolving door for staff, she said.

“When you put those two things together, this risk to John David is significantly increased. He only has 25 per cent lung capacity on the left and 50 per cent on the right. I don’t want to think about what would have happened to him if he had been forced into a group home before Covid. I truly believe I would have lost him,” she said.

“These Medicaid waivers were created to enable the developmentally disabled population to live in the least restrictive environment, choose where they live, who they spend their time with and who takes care of them. The proposed change to the waiver takes all their choices and freedoms away,” she said.

John David’s condition requires 24-hour care with two caregivers. One must either be an LPN or family member trained in CPR, administering medications and tube feeding, and suctioning fluid from his lungs.

“I already do 12 hours of care a day, plus cover every shift when staff calls out sick. Now I’ll need to do hands-on care 20 hours a day. When would I work, sleep, or grocery shop? I never leave the house as it is, and I rely on family or friends to shop for us. I wonder how the state expects us as family members to do that number of hours? The answer is, they don’t. They put us in a position to where we don’t have a choice, except to put them back into state-run homes. But I won’t do that to my brother.”

“I’ve already put my home on the market. I need to downsize so I will have a lower house payment that I can afford only working part time, and care for my brother at home the best I can.”

Georgia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities supports more than 13,000 Georgians with intellectual and developmental disabilities through several Medicaid waiver programs. Another 7,000 Georgians are on the waiting list for support, with many residents languishing on the list

The number of medically fragile Georgia residents who are at risk of relocating from their homes to a group home or nursing facility is presently 187, according to disability advocates who are fighting the proposed budget cutbacks.

Judy Fitzgerald, DBHDD Commissioner, has acknowledged that change is difficult and scary, especially for those with disabilities and their families. “One thing will not change,” she said. “DBHDD is required and strives to meet the needs of every individual who receives waiver services.”

For those who will experience changes, Fitzgerald said that she, her team, and network of providers will work to ensure everyone’s services are designed in a person-centered and collaborative process that empowers them to live safely and independently.

Instead of the 24/7 care previously available under the Community Living Support (CLS) program,the department has proposed limiting services to a six-hour maximum daily authorization for

additional staffing services and a 16-hour maximum daily authorization for skilled nursing services, notes Shelly Dollar, a Georgia disability advocate and parent of a profoundly disabled young woman. “Georgia residents who require more than the new limits would be redirected to group residences,” she said.

While Archibald acknowledged that state budget cuts are necessary, she has asked DBHDD officials to look into fraud and waste first. “Instead of butchering the budgets to the most vulnerable of our community, they could take a look at the entire budget and use a scalpel to make the needed cuts,” she said.

Story and Photographs © Robin Rayne/Zuma

Mike and Sheila McBroom often lie awake at night, filled with anxiety about their disabled adult son Tim’s future.

Tim, 36, who is non-verbal and experiences severe autism, has seizures and behavioral issues. McBroom and his wife are doing their best to provide their son with a safe and secure environment in their Jonesboro home, with daily help from Medicaid waiver-funded support staff.

But proposed cutbacks to those Medicaid-funded services turn their son’s life upside down.

Georgia’s disability officials are currently wrestling with likely budget cuts that will dramatically impact their son, and 187 others in the state with profound intellectual disabilities who need extensive daily support to remain at home.

“We’ve been able to keep him at home for the past 21 years with supports from the waiver. Tim requires a lot of support and has always had a lot of service hours. That’s the only thing that allows us to have any semblance of a normal life outside of caring for him,” explains McBroom, 65, “but that could change any day, and we feel powerless to do anything about it. The state’s solution is to place Tim and others like him in group homes. That would be a disaster.”

Georgia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities supports more than 13,000 Georgians with intellectual and developmental disabilities through several Medicaid waiver programs. Another 7,000 Georgians are on the waiting list for support, with many residents languishing on the list for years.

The McBrooms are deeply angered at the state’s proposal, especially considering Georgia was the birthplace of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Olmstead Decision in 1999. The court ruled that individuals with developmental disabilities could no longer be isolated and segregated from society in institutions. That population was to be integrated into communities when possible, with services provided where they lived. State-owned institutions for the developmentally disabled subsequently closed, and residents were relocated into a confusing and overwhelmed system of skilled-care facilities, group homes, and private residences. “Person-centered planning” and Medicaid-funded supports resulted in significant quality-of -life improvements for those were able to live in their own homes or with family members, disability advocates said.

“The court ruling was seen as a landmark decision for the disability community, but with Georgia’s proposed budget cuts, many families fear the state is returning to pre-Olmstead mindsets,” Sheila McBroom said.

Georgia’s proposal that Tim and others like him be relocated back into group homes flies the face of what the Supreme Court ordered, she said. “It’s a step backwards for the disability community, and Georgia should know that better than anyone.”

The state’s proposed cutbacks affect 187 individuals like Tim who need more than 16 hours a day of support that allows them to remain at home, integrate into their communities, and enjoy some degree of independence, Mike McBroom explained. “Under proposed changes to the waiver, Tim will no longer qualify for the person-centered care he needs to remain here,” he said. “State officials said they have identified the needed numbers of beds in various locations around the state — and all of them are in group homes.”

“This proposal affects Georgia’s most vulnerable citizens and jeopardizes their ability to live in the least restrictive community setting because of their cognitive and physical conditions,” notes Shelly Dollar, an Atlanta mother of a 31-year-old woman with profound disabilities who requires 24-7 in-home care. “They will lose the care they require to live their best lives,” Dollar said.

“The state tried to push the group home option in the past,” Mike McBroom recalled. “We were involved with group homes years ago. We’ve also had many caregivers who worked in group homes. We’ve seen and heard of too many situations that should not be acceptable. The state has had many group home deaths they cannot explain. We’re aware of cases where the clients died due to poor or lax attention to issues before they became an emergency.”

Dollar called the state’s proposal a “one-size-fits-all approach where individuals are essentially herded together.” The time when developmentally disabled individuals were segregated away from the rest of society is over, and forcing them to move into institutional-group home settings “is not only inappropriate, it is just wrong,” she said.

The Comprehensive Supports Medicaid (COMP) waiver is one of two under Medicaid authority. It is administered by Georgia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disability. “That agency’s mission is to empower individuals with developmental disabilities to live safely and independently in their communities,” McBroom said.

The waiver must be renewed by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services every five years. Georgia’s waiver program expires in March. Ashley Fielding, assistant commissioner at DBHDD, said her office is reviewing services that aren’t widely used, redirecting resources into areas where demand is higher.

“They are taking from one pocket and spreading it around so that it looks like they’re doing more than they really are. 187 Georgia residents with serious disabilities who really need the support will pay the price, and it’s all about appearances,” McBroom said.

“Some of them have become self-injurious and/or aggressive with others when forced to live in a group home setting,” Dollar said. “They can’t tell you why aggregate living situations don’t work for them other than by their acting out behavior for which they are typically punished by those who should be their advocates. It’s heartbreaking.”

Even with the support Tim McBroom has, he falls with caregivers and has seizures where the caregiver didn’t know how to respond, McBroom explained. “We have seen him lose ground when caregivers do not ask questions or pay attention to his history. And that’s with current levels of support. It would be far worse in as group home.”

Tim currently has slightly over 12 hours per day staffing, McBroom said. “This allows them to get out with him during the day and have time to get him settled at night. There is a second person when they are out in the community and that is 7 hours a day. This gives them time to do productive activities, and it allows us to be able to have some time for ourselves.

With the proposed limits on hours, we would lose the ability to have a normal life and Tim would be stuck in the house longer than he is now. We are trying to support Tim with the waiver assistance as long as we can,” said McBroom, who suffered a small stroke brought on by stress.

Judy Fitzgerald, Commissioner of Georgia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities, has acknowledged that change is difficult and scary, especially for those with disabilities and their families. “One thing will not change,” she said. “DBHDD is required and strives to meet the needs of every individual who receives waiver services.”

For those who will experience changes, Fitzgerald said that she, her team, and network of providers will work to ensure everyone’s services are designed in a person-centered and collaborative process that empowers them to live safely and independently.

Instead of the 24/7 care previously available under the Community Living Support (CLS) program,the department has proposed limiting services to a six-hour maximum daily authorization foradditional staffing services and a 16-hour maximum daily authorization for skilled nursing services, Dollar explained. “Georgia residents who require more than the new limits would be redirected to group residences,” she said.

Dollar and the McBrooms firmly believe such a relocation into quasi-institutional settings would traumatize their children, with devastating results, including higher risk for injury, mistreatment, and abuse.

“We will be forced to put him into a group home where quality of care is not guaranteed. Tim would have little say in his everyday activities. Many group homes are one step above an institution and with the low pay and low training requirements – not somewhere where we can expect the best quality of life for any consumer,” McBroom said. “If we place him in a group home, they want to control everything. If there are dental issues, they will only get a tooth pulled, since Medicaid will only pay for extractions and not preventative care.”

“As we age and after our passing, we will need safe, enriching options for Tim to live and thrive. The state always has voiced a desire that all plans be person-centered and should improve the quality of their lives,” McBroom added. “For us to be put in the position that we may have to consider a group home because we can’t get the support we need goes against every bit of this.”

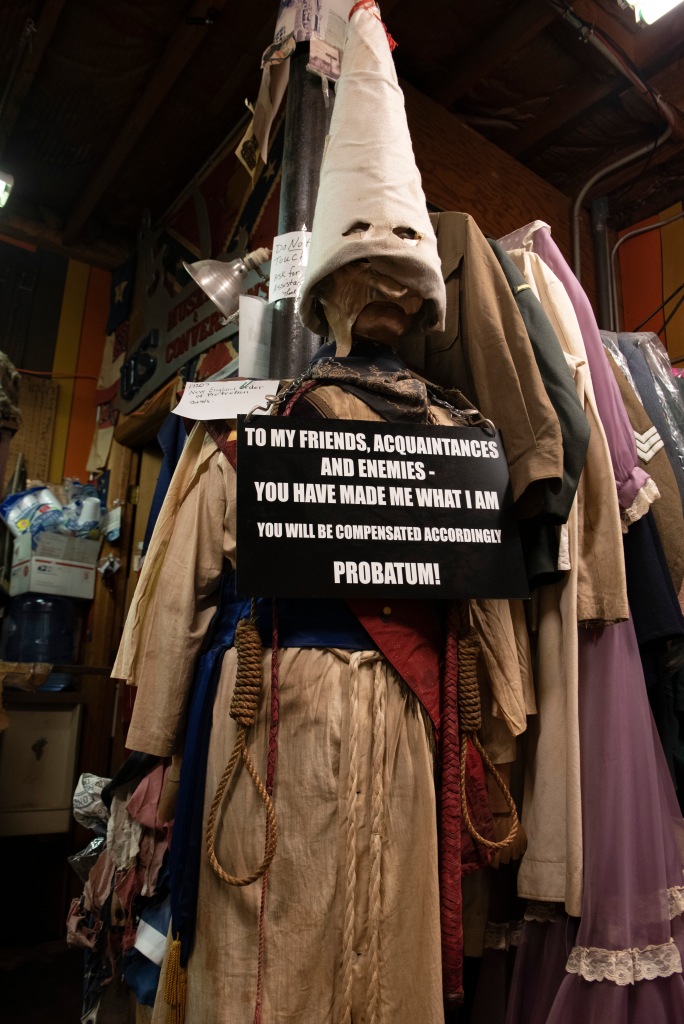

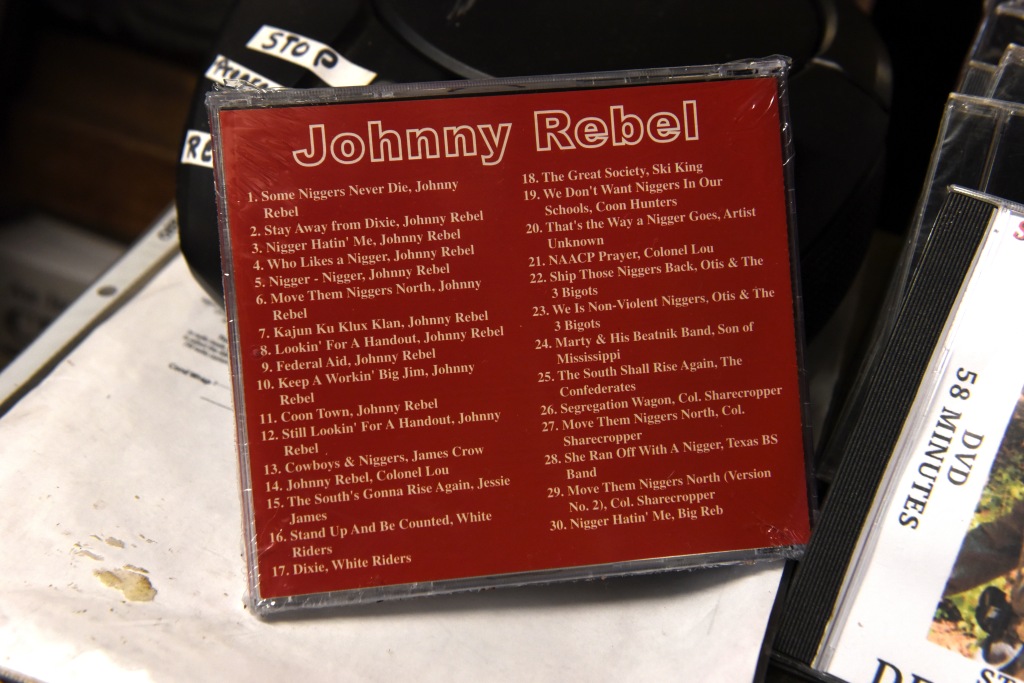

The Last Confederate’s ‘Last Stand?’

Dent Myers is a living anachronism in Kennesaw, Georgia, harkening back to a time when the American Civil War nearly ripped the nation apart. His friends are worried about his well-known ‘Wildman’s’ Shop’s survival in the current Black Lives Matter climate.

Story and Photographs ©Robin Rayne/ZUMA Press/All Rights Reserved

Kennesaw, Georgia – For Dent Myers, the ‘war of northern aggression’ still smolders.

“It’s all history, and people need to learn it and know it. They don’t teach history in the schools anymore, and it shows in what little people know about it now,” said Myers, 89, a former re-enactor and Korean War veteran who has a memory of Civil War facts and strategies that could challenge the most learned history professor.

He was born to poor sharecropper parents in rural Georgia, and grew up without electricity or running water. “We had a two-hole outhouse, and we thought we were doing pretty good,” he joked. “We grew our own food and bartered for what else we needed. I didn’t even know what money was until I was seven years old,” he said.

The crusty history buff opened Wildman’s Civil War Surplus shop in Kennesaw, Georgia center in 1971.

“It was a sleepy little town with a lot of history,” Myers recalled. He sports a long and scraggly beard and a fistful of hammered silver rings on his fingers. He might wear a bandana on his head one day, and a beret the next. While the aura of an aging hippie from the 1960s surrounds him, Myers was a more mainstream-looking engineer for the Lockheed-Martin Aircraft plant in nearby Marietta in those years.

The town of Kennesaw received international attention in 1982 after the city council passed an ordinance that required all citizens to own a gun and ammunition. Kennesaw was nicknamed “Gun Town, U.S.A” and stories were published worldwide about the controversial law. Myers happily agreed to scores of interviews and photos, often brandishing a pair of .45 caliber pistols he typically wore in holsters strapped to his waist, like a gunslinger from the wild West.

Myers’ story and photos have continued to be shared in newspapers and magazines in dozens of countries and languages in the decades since. “We get people from Germany and Japan and Norway and just about every country coming to see us in the flesh. They read about us and want to see if we’re for real. They want to see that KKK robe in the back. It’s history. Everybody knows Wildman,” he quipped. “Some people call me the village idiot,” he joked.

His very presence — and disdain for ‘political correctness’ — continues to irritate hundreds of activists and protesters who insist his store and opinions promote bigotry and racism. “There’s a bunch of them who would love to burn this place down,” he said. “They want to run me out of town on a rail. There’s even kids on the school bus who talk about setting fire to this place, but they just learn that from their parents, and most of them aren’t from here. They want to bring their New Jersey ways to Georgia. But I’m not going anywhere.”

A yellowed Ku Klux Klan robe from the 1920s and homemade hood that served as a movie prop are displayed near the back of his museum. Myers won’t admit to being a Ku Klux Klan supporter. “I’m not much of a joiner,” he admitted. But the man who often referred to young black children as ‘Niglets’ has been called a racist, redneck, and honky bigot, among others. “I just let it slop off me like a proverbial duck, except my feathers don’t get ruffled,” he said.

Now frail with advanced age and blind in one eye, Myers shuffles about his relic and antique shop to chat with first-time visitors. Local ‘regulars’ come and go throughout the day to hang out inside the cluttered shop or sit on benches outside where they share war opinions on current events. Many just come just to pass the time on a lazy afternoon with others who revere the Southern culture and Civil War lore. “Most of them come packin,” Myers said with a wink, as his hand brushed the holstered Colt .45 on his hip.

Local residents either embrace him and his love of history or despise him for his racist views. In 1993, the Kennesaw Historical Society awarded him its first Historic Preservation Award, but in recent months his shop has been the focus of vehement protests urging the city to force him to close. The demonstrations were spurred by Black Lives Matter organizers who believe Myers’ time has come to fade into the sunset.

His dust-covered shop is filled to the ceiling with photographs, papers, uniforms, maps, t-shirts, bumper stickers, flags and long-forgotten boxes of relics accumulated over nearly fifty years. His treasures once included a small box of cotton balls labelled “Niglet Repellant” he said was intended as a joke. “Somebody told me they won’t pick cotton because they’ve gone upper-class now,” he explained.

His shop also displayed a collection of CDs with titles including “Coon Town,” “The South’s Gonna Rise Again,” and “ Segregation Wagon” among the song titles — content that causes even some of Myers’ more ardent supporters to cringe.

“That’s exactly why Myers and his shop needs go,” said one town resident who is pushing to get Myers to close his business. Calling Myers an outdated, racist relic who needs to ‘go away,’ nearly 100 Black Lives Matter demonstrators recently gathered outside his shop to vent their anger.

“He’s an embarrassment to this town,” explained Parker Quigley, one of the protesters. “His store gives the impression that he keeps racism alive.”

Another protester wants Myers to be humiliated. “He has cognitive dissonance and he won’t pay attention to what’s going on around the country,” said Jamie Forsyth, 17, who lives in nearby Acworth.

“Just get rid of it all. I don’t give a f*** about that history. It wouldn’t bother me to see the place burn to the ground.”

“In this politically correct time, people don’t want to have anything to do with the Civil War, and especially the Confederacy,” notes Joe Bozeman, 75, who’s known Myers for more than 50 years. “There’s a hatred for what they call the Old South, and they would like to forget the Civil War ever happened,” said Bozeman, whose great-grandfather fought in the war. “They’re under-educated, and they don’t know this country’s history.”

Liberal college students from nearby Kennesaw State University think it’s cool to protest, he said. “There’s some folks who would just as soon whitewash all the history out of Kennesaw and make it look like some little town that looks like everywhere else,” he said.

Myers and his friends take the criticism in stride and view the protests with a sense of humor. “Most of them haven’t even been inside this place,” Myers said. “They’re only repeating what they’ve been told to say. They should ask for their tuition money back because college didn’t do any of them much good. They didn’t learn much.”

Myers said he could easily enlist the aid of dozens of friends, many of them military veterans who would welcome the opportunity to stand guard outside his shop when the protesters show up. “But I don’t want to do that because that’s just what the protesters want. They want to engage, and it would get ugly real fast. Nobody needs that,” he said.

Myers owns the two-story building that houses his shop, which annoys several city officials. He’s well-aware of the mounting pressure for him to leave town. He knows the current political climate might create his last stand for the shop’s survival.

“But I pay my taxes and I don’t do anything illegal. I’ve done more to bring tourism to Kennesaw than anything they’ll ever do,” Myers said.

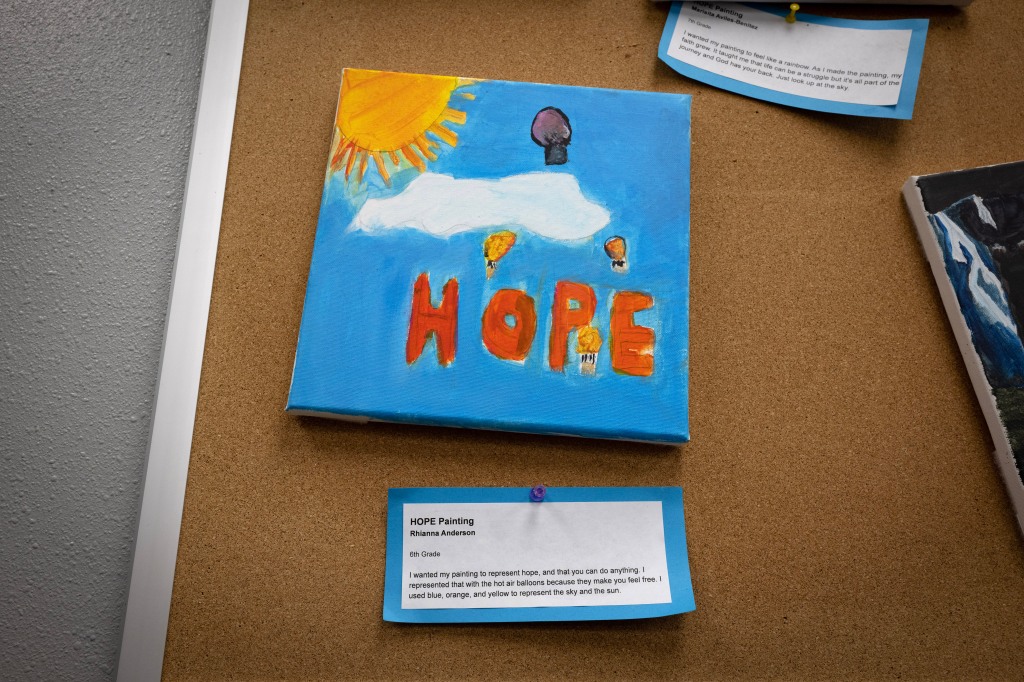

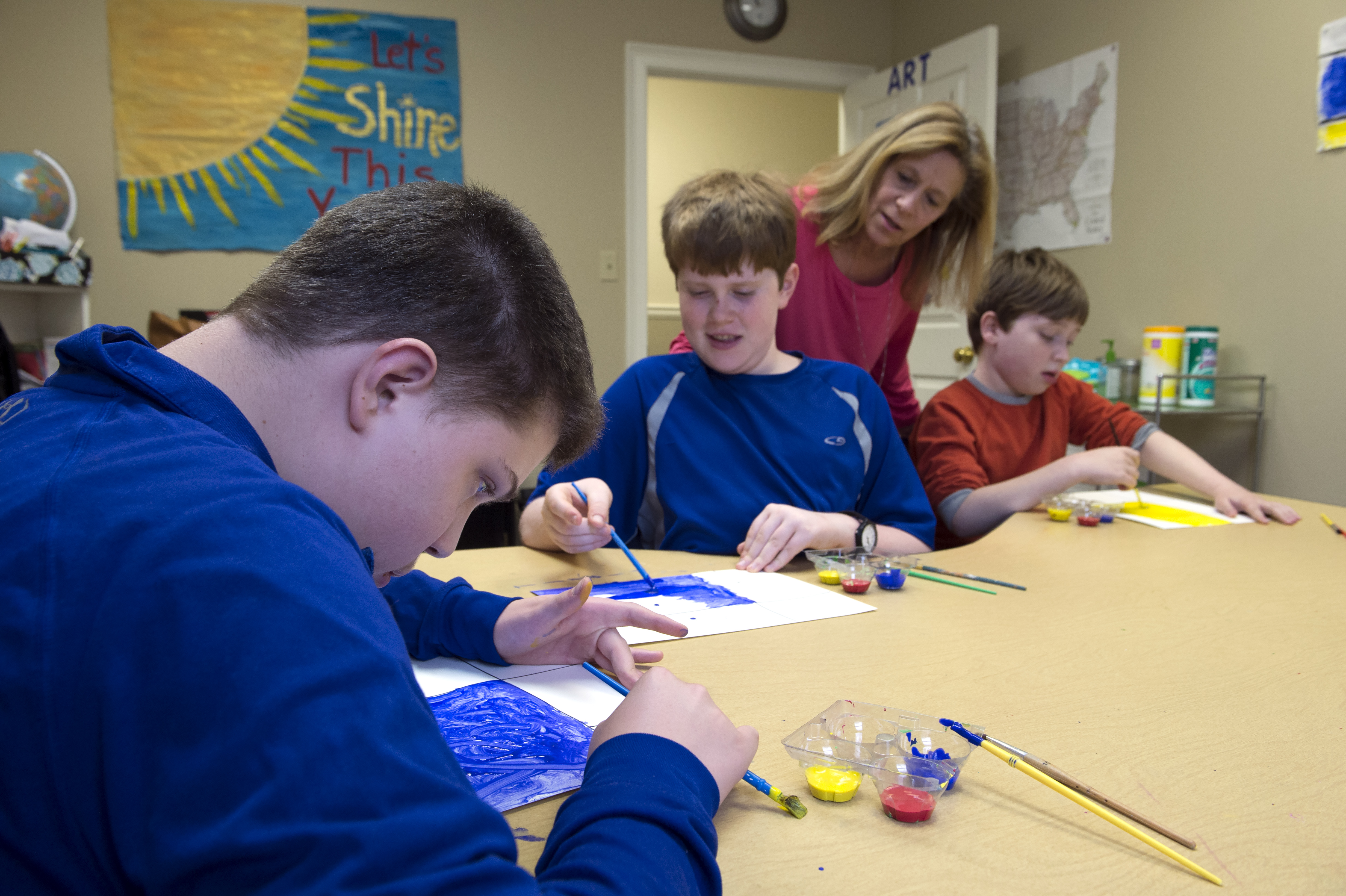

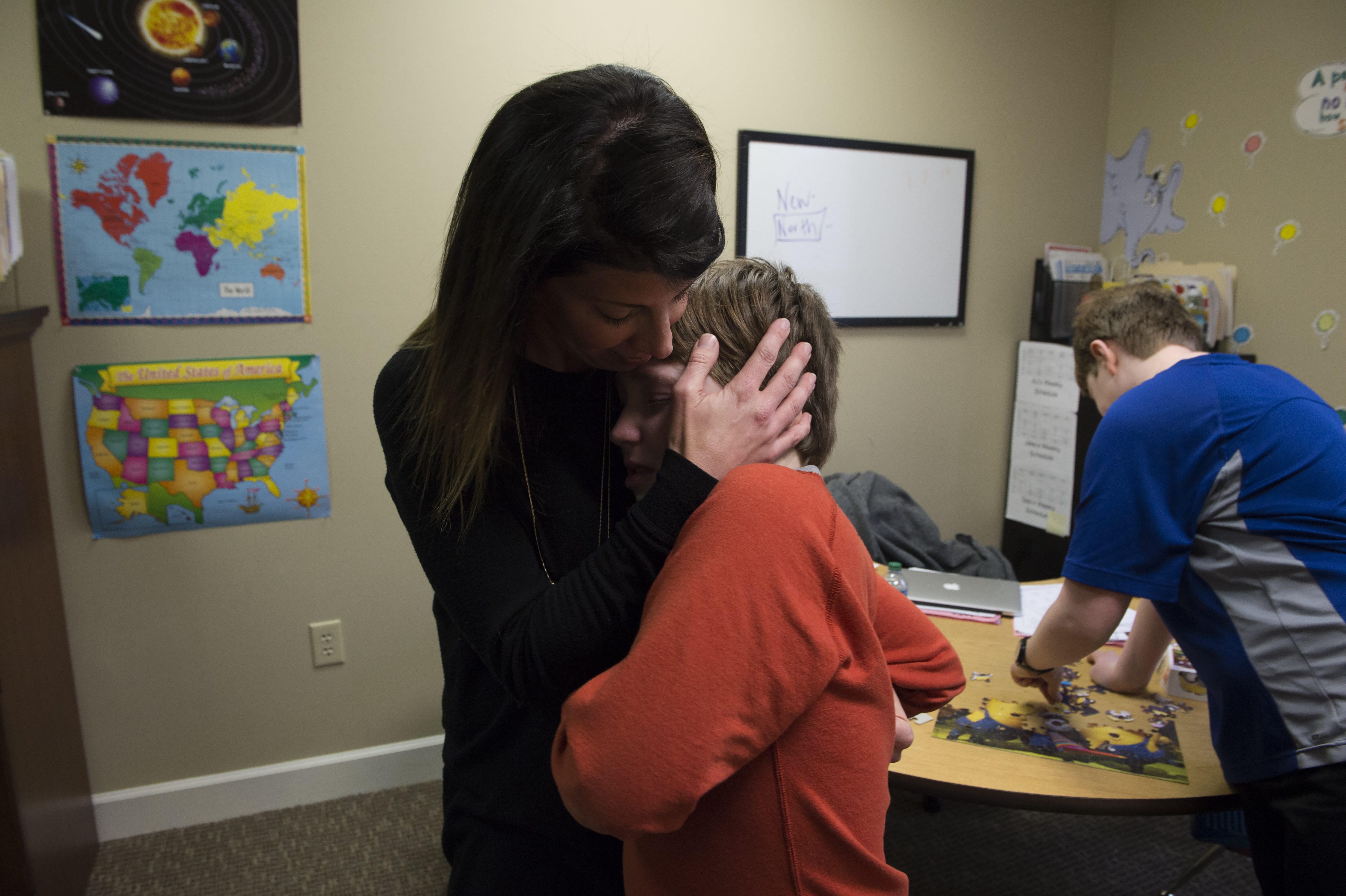

A Helping Hand for Students Who Learn Differently

Story and photographs ©2019 Robin Rayne/ZUMA

Marietta, Georgia — Mindy Elkan knew her speech therapy clients with learning challenges and developmental disabilities needed more than what public school special education programs provide.

“The public schools can only do so much,” the Marietta speech therapist said, remembering the time ten years ago when she decided to start a small private school herself. “I always wanted to open a school for children with communication disorders.”

Elkan, 62, opened the MDE school in 2009, named to honor her late husband Mark David Elkan. “I was inspired to keep his legacy and his memory alive by establishing a school for children who learn differently. He loved children and was always there to help at the clinic,” she said. Mark Elkan, who died in 2009, often volunteered at hippotherapy sessions at area stables as well as community walks to raise public awareness of autism, she said. “His heart was always open to any individuals who needed help — especially children.”

Elkan’s school started small, with classes held in her Marietta speech therapy office.

“We began with three students and one part-time teacher. Our goal was to help families who were home-schooling their children with learning disabilities. It was like home-school away from home,” she said. The school added four more students the next year, with 17 students and a third teacher added in the school’s third year, she said.

Ten years later, MDE School has 49 students and a full-time staff of 19, tucked into quiet office park in east Cobb County. The school prides itself on providing a loving and nurturing environment.

“It’s what Mark would have expected,” Elkan said.

Tuition is $21,000 per school year, but financial assistance vouchers and scholarships are available from the state and county, Elkan said.

The students’ challenges range from autism, Down syndrome, cerebral palsy and other developmental disabilities to language and communication disorders. Several students are non-verbal, and a few experience seizure disorders. Student works at their own pace. Teachers work closely with parents to create individualized educational plans designed to meet each child’s exact needs. The school is accredited from kindergarten through eighth grade. Life skills and prevocational training are offered for high school-age students.

Elkan received her master’s degree in speech and language pathology from Hofstra University in New York before relocating to Georgia in 1990.

With a ration of four students to every teacher, the school provides smaller classrooms, flexibility and one-on-one instruction. Teachers recognize the value of enrichment programs and coordinate with the community to bring yoga and dance sessions into their schedules, as well as golf, cooking and Lego clubs. Students are also integrated into the community with regular visits to restaurants and a variety of local businesses.

While the school focuses on academics, art, music, life and social skills and prevocational training are considered equally important parts of the school day, she said.

“Students are taught basic life skills – simple things like brushing their teeth, setting a table, making coffee and doing their laundry to ordering food at restaurants and interacting with people.

“Social skills are very important,” Elkan stressed. “We are preparing them for life.”

Anita Newby’s son John Michael, 16, is in his fifth year at the school. “He had a very difficult time in the public schools because he has complicated language and processing problems and needed a very focused type of instruction.

“John Michael didn’t speak until he was eight years old,” she said. “It’s still difficult to understand him sometimes, but the tiny size of the classes and one-on-one time with his teacher helps him a lot. The classes are customized to provide what each child needs. It means so much t to have your child happy and learning in school,” she said.

Kick-off Time at Atlanta’s Super Fest

Story and Photographs by Robin Rayne

They came to pass, punt, tackle and cheer on Super Bowl weekend, with passion and determination worthy of any NFL team.

Less than a mile from Atlanta’s Mercedes-Benz Stadium where the actual 2019 Super Bowl game would unfold before millions, this inclusive football and cheerleading clinic known as Super Fest was underway for more than 120 children and young adults with developmental and other physical disabilities.

Cheerleaders from both the New England Patriots and Los Angeles Rams teams were on hand to greet, teach and encourage all who came to the Georgia State University football practice field. They were joined by volunteer coaches, athletes, and alumni from the Atlanta Falcons, local universities and the National Football League.

“Our goal was to provide a realistic and enjoyable experience to individuals with disabilities and their peers, enabling everyone to participate in the excitement of the Big Game weekend,” explained Jessamy Tang, Super Fest’s organizer.

Tang, a former sports media executive for ESPN, and husband John Blascovich, a business executive, created the Mathew Foundation as a non-profit organization to improve lives for persons with Down Syndrome. They named it after their ten-year-old son Matthew, who has Down Syndrome.

“It is a private charitable foundation that strives to make a meaningful impact for persons with Down Syndrome, one program at a time,” Tang said. “We believe in collaboration within the national and global Down syndrome community as well as externally with both governmental and non-governmental organizations,” she said.

Tang, her husband, and foundation directors strongly believe the rights of children with disabilities to all forms of physical activity and sport are often not being realized, although they are enshrined in numerous legally-binding documents and are well-known components of healthy child development, health maintenance and chronic disease prevention.

Tang, 51, worked in sports radio media at ESPN for many years and cultivated numerous connections to celebrities, players and coaches in the pro-sports world. The Matthew Foundation organized Super Fest as an annual event to be hosted in the same city and week as each year’s Super Bowl, and is open to all youth and young adults.

Start writing or type / to choose a block

Happy Hearts and Tears of Joy For All at This Pageant

Dressed in formal gowns, Contestants lined up on stage as they waited their turn to greet the judges.

Story and Photographs ©2018 Robin Rayne/ZUMA Marietta Daily Journal

Marietta, Georgia — With smiles and confidence filling the stage, thirty excited and happy contestants strolled, glided and twirled before a table of pageant judges in the Equestrian Center at Jim Miller Park on a cool September night, hoping to be named Pageant Queen or King.

It was the North Georgia State Fair’s first Special Needs Pageant, and every contestant won hearts and brought on the tears from the enthusiastic crowd and judges alike.

“This was our first pageant for the special needs community and we hope it will be an annual event at the fair,” explained Renee Fielden, a retired Coca-Cola executive who directed the event. It was produced by the Miss Cobb County Pageant organizers and was open to all, at no cost.

Julie Denton, from Kennesaw, Georgia, escorts her son Christian, 9, across the stage after greeting the judges.

“All credit is due to Tod Miller, the Fair Manager. He wanted to do something to highlight the Special Populations Day at the fair,” Fielden said. Miller reached out to Terry Chandler on the Fair Board and Gene Phillips, President of the Miss Cobb County Pageant about producing the pageant. “I’ve been involved in pageants for many years, and I was honored that they asked me to be the director,” she added.

Contestants were judged on attire and personality. The winners in each division were awarded a specially designed Fair Jacket with the King & Queen of the Fair logo, along with four VIP passes to the fair, she said. Everyone who participated received a pageant t-shirt.

“There are not many special needs pageants in the area, so this gives everyone an opportunity to participate and showcase their wonderful personalities,” Fielden said.

Mandy Hoopingarner, 36, from Powder Springs, Georgia, waits for her cue to dance before the judging panel.

Gracie Randall, 6, from Kennesaw, Georgia, blows kisses to the judges

A young girl with limited vision is guided by her mother to a mark on the stage where she met the judges

Al Cosby, from Dallas, Georgia,, kisses his 5-year-old daughter Chesney before he carries her onstage.

Contestants in the Junior Queen category assemble on stage as winners are announced.

The contestants wave to the enthusiastic crowd as they wait for results.

A place for homeless veterans to lay their heads

Photo and Story © Robin Rayne/ZUMA

MARIETTA —Veronica Sigalo knew she had to do something to help the homeless population, even if it was for just a few individuals at a time.

As a nurse at the DeKalb County jail, she watched as inmates were brought to the jail, released — yet returned the very next day.

“I ask them, ‘Why you come back?’ They say they need a place to stay, especially in winter, so they do stupid stuff so they can come back and have some food and stay warm,” said Sigalo, 58, who emigrated from Nigeria in 1986 and worked as a licensed practical nurse for several years.

“Where I come from, going to jail is taboo. Nobody wants to go to jail. I talked about it with my friend who also worked at the jail and we decided to do something. As we got more involved with the homeless we decided to start a non-profit to help — but we had no idea how to do it,” she said. “I remember thinking, ‘If God wants us to do it He will show us the way.’ God led us to see all the people who are homeless and see how others are helping,” she said. “We do it by ourselves, step by step, to start the non-profit.”

Sigalo launched Zion Keepers in Marietta in 2005. The faith-based non-profit organization provides housing and other supportive services to homeless disabled male veterans, people living with HIV/AIDS, people struggling with mental illness, substance abuse, and other life controlling issues.

Zion Keepers currently provides subsidized housing in a Marietta apartment complex for nine veterans who would otherwise be homeless. Sigalo said she hopes to add temporarily living space in Smyrna that would accommodate another six veterans.

Though she lives in Stone Mountain and recognized the increasing need throughout the Atlanta metro area, Sigalo said she felt led to open her non-profit office in Marietta.

“There was a great need in Cobb County for veterans. I always thought I would go into ministry, but this is where I’m called to serve,” she said.

With funding from federal Department of Housing and Urban Development, Zion Keepers was initially able to provide living space for 18 homeless veterans in six apartments on Franklin Road near Interstate 75. Recent budget cuts caused the non-profit to downsize to three apartments and relocate a few miles west.

Residents are required to pay $400 each for rent. Zion Keepers pays all utility bills.

“We didn’t start out just serving disabled veterans, but there were many veterans in the program. Now the Veterans Hospital calls if they have someone in need and they ask if we have room for him,” she said. “If we do, he has a home for as long as he needs it.”

Homeless Population Difficult to Count

Veterans become homeless from a complex set of factors such as severe shortages in affordable housing, poverty, high unemployment and mental and physical disabilities, Sigalo said. A large number of displaced and at-risk veterans live with the lingering effects of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and substance abuse, compounded by a lack of family and social support networks.

While accurate numbers are difficult to assess, Veterans Administration officials estimate that more the 200,000 veterans are homeless on any given night nationally, with more than 400,000 experiencing homelessness over the course of a year. At least one out of every four individuals who is sleeping in a doorway, alley, or cardboard box in cities and rural communities has put on a uniform to serve in the military, and nearly half of all homeless veterans served during the Vietnam era, VA officials note.

A 2017 report prepared by a coalition of advocates for the homeless lists 403 individuals in Cobb County as either ‘sheltered,’ ‘unsheltered’ or living in ‘transitional housing.’

Advocates define ‘sheltered’ individuals as those who live in domestic violence and emergency shelters, or motels or apartments paid with vouchers by public or private agencies because the person is homeless.

‘Unsheltered’ individuals live in places not designed for human habitation, such as abandoned buildings, park benches, under bridges or in illegal makeshift camps in wooded areas.

‘Transitional housing’ provides living support for homeless individuals or families, with the goal to facilitate independent living within 24 months, unless approved by HUD for a longer period.

Official numbers provided to HUD are often incomplete because of different barriers to obtaining comparable data, advocates for the homeless said.

“If someone is living in a hotel, HUD says they’re not homeless,” notes Kaye Cagle, a spokesperson for MUST Ministries in Marietta. School systems might classify a student as homeless if they live in a hotel, she said, noting different definitions of the term.

“We have 200-300 unique individuals that we turn away from our shelters every month,” due to space limitations, notes Chris Fields, executive vice president at MUST Ministries. “For the first time since we began measuring, the largest percent of the total of those are children at 38 per cent.”

The actual homeless population in the county is generally thought to be at least five times higher than the survey count, MUST officials estimate.

As shelters close and rents escalate in urban areas, more and more individuals find themselves pushed out to suburban towns to survive, advocates said.

Sigalo said homelessness has become less of a priority with government officials, “but is still very much with us as a problem. Funding is so much more competitive now, but we hope to get back to where we were when more funding is available,” she said.

Sagalo now works with a staff of three from a small, sparsely-furnished office in Smyrna. “We sometimes work without pay, like a church. I have good children who are grown who help us keep going,” Sigalo said.

Sagalo now works with a staff of three from a small, sparsely-furnished office in Smyrna. “We sometimes work without pay, like a church. I have good children who are grown who help us keep going,” Sigalo said.

“I wish more people knew we exist,” Sigalo said. “We can’t do anything without funding. We need more volunteers who could help, and we could use a van to get the veterans to appointments.” The veterans typically use public transportation for visits to the VA Medical Center in Decatur, with trips often taking several hours each way, she said.

*****

Donald Lewis O’Neal, Fletcher Thompson and Tony Salomone share one of Zion Keepers’ three apartments in Marietta.

O’Neal, 70, grew up in Atlanta and served as an Army radio communications specialist in the Central Highlands of Vietnam in 1968-69. “I was in the jungle, I was the link between the front lines and the command. I was friends with guys who went out on patrol but didn’t make it back. It’s really hard to talk about it,” he said. O’Neal lived with relatives for many years but eventually found himself on the streets. “Life didn’t go so good,” he said. He connected with Zion Keepers earlier this year.

Thompson, 69, was an engine technician and tester for the Air Force in the 1960s. “I was a sergeant, stationed in the U.K. along with the Royal Air Force. When I got out I worked for K-Mart as a store manager, but I was an alcoholic,” he said.

Hospitalized for eight months in 2013, Thompson said he nearly died twice.

“God let me live but I lost all my things. I went to the VA and told them I was homeless and needed a place to stay. I only had a few dollars in my pocket.” Thompson moved into a Zion Keepers apartment in March.

Salomone, 62, served three years as an Army communications specialist in Texas and works as a maintenance person for a local assisted living facility. “I had a job in Canton and I had my own place to live, and then the company I worked for went out of business. Things fell apart after that,” he said.

Salomone, 62, served three years as an Army communications specialist in Texas and works as a maintenance person for a local assisted living facility. “I had a job in Canton and I had my own place to live, and then the company I worked for went out of business. Things fell apart after that,” he said.

“I lived in a motel on Highway 41 for a few months and then a friend told me about Miss Veronica. I’ve been here four years,” he said.

He is grateful for what Zion Keepers provide but looks forward to a day when he can live in his own apartment again.

“Once you reach a certain age getting a job is really tough. Getting a place is really tough. This country is not made for the old. I see that every day where I work with people who have the money. If you don’t have the money, it’s tough luck.”

Unwelcome in the Neighborhood

In October, 2017, Cobb County commissioners agreed to lease its Rose Garden facility on Teasley Drive in East Smyrna to Zion Keepers for an initial five-year term.

Sigalo plans to open the facility later this year as a day center, with room for a food bank, counseling services and limited transitional housing for six disabled veterans. Veterans could stay could stay for up to a year as they get their life back together, she said.

The building was deeded to the county by the Cobb County Healthy Futures Foundation in 2010 and housed a learning center for underperforming elementary students until that business ceased operations in 2016.

Zion Keepers will be responsible for all facility repairs, maintenance, upkeep and improvements to the property, as well county-approved insurance coverage, Sigalo said.

Zion Keepers will be responsible for all facility repairs, maintenance, upkeep and improvements to the property, as well county-approved insurance coverage, Sigalo said.

But residents in the Rose Garden neighborhood are angered about Sigalo’s plan to move into the currently-vacant building. More than fifty neighborhood residents met with county commissioners in February to voice their intense opposition.

“What happens if they decide to go crazy? They could become violent,” warned Emily Norwood, 22, who served as a boatswain’s mate in the U.S. Navy. She and her veteran husband live with their year-old toddler son Caysen next to the currently-vacant property. “I shouldn’t have to be worried at night that someone from the shelter comes into my house. Bringing in strangers, there’s a higher chance of something happening.”

“It’s nothing against veterans, but the odds of them all being okay are very small. They’re probably great guys, but that’s a lot to throw at a neighborhood,” said Scott Bagwell, 58, who also lives nearby. “We don’t want it. We just don’t know what we’re getting into. It would be hard to fit into this community,” he said.

Bagwell fears veterans’ post-traumatic stress disorder breakdowns could be triggered by sounds of low-flying aircraft from nearby Dobbins Air Force Base. “The unknown is the problem. They could go off their medications. There’s children playing around here. What are they going to do all day? It’s a safety thing and a big potential threat,” Bagwell said.

‘Fear is the Enemy’

Those comments make Sigalo sad.

“They are coming from fear,” Sigalo acknowledged. “They don’t want to hear that these veterans served their county. It is like they do not care. Most of the population we see is age 54 and up. These veterans should be at home with their families, especially the aging ones. My heart is in helping these veterans stay off the street. They fought for us and they help make this country what it is,” Sigalo said. “The least we can do is help them when they are down.”

Commissioner Lisa Cupid listened to the residents’ concerns at the February meeting. “This neighborhood has had its fair share of challenges and feels like it has been overlooked,” she said. Cupid’s district includes the Rose Garden neighborhood.

While she supports Zion Keeper’s mission to serve disabled veterans, she conceded that the Rose Garden community was not provided reasonable notice and participation in the leasing decision. “We are asking this visibly vulnerable area to bear the weight of an unmet social issue pertaining to transitional housing of a vulnerable population. It might not have been made clear to everyone exactly what Zion Keepers’ plan included,” Cupid said.

Cupid said it was not unreasonable for any residential community with a proposed transitional group home of six or more people to have questions or concerns about the impact a group home will have in their community.

“Serving veterans is an honorable and critically needed service,” Cupid said. “I think Zion Keepers does great work. Once the neighborhood sees who they are and who they serve, I think they will be more supportive.”

Cupid said she wants to be fair to both the Rose Garden community and Zion Keepers, and hopes the building can be used in a way that serves both.

Sigalo said she is waiting for the county to complete roof and gutter repairs before opening its doors over the summer months. She plans to offer services to the community including counseling and a food bank initially but will delay adding living space for veterans for the present. “We need to gain the community’s trust first,” she said.

Chris Hernandez: A Musical State of Mind

Chris Hernandez conducts school orchestra in performance of his work, “Ciadudela”

Story and Photographs ©2018 Robin Rayne/ZUMA Press

Chris Hernandez can’t stop the music.

“I always have these tunes playing in my head,” says the 17-year-old musical prodigy, a junior at Kennesaw Mountain High School who made his debut as both composer and conductor at the school’s recent Spring orchestra concert.

Music has been a part of his life since before he was born.

“I hear these tunes that are similar in rhythm, melody, and chromatic structure. They just come to me and I write them down. That’s how I come up with these compositions,” explained Hernandez, whose original piece “Ciudadela” recently premiered in the school auditorium to a standing ovation from the capacity audience.

The title is Spanish for citadel, he explained. “It represents a state of mind where everything is as expected,” he said. The score was heavily influenced by Latin music his father played for him as a child and was Hernandez’ third musical composition — with a promise of many more to come.

Hernandez lives with younger brothers Richie and Jacob, and parents Ricardo and Sandra in West Cobb County. Chris is a magnet student in the high school’s well-respected instrumental music program.

School Orchestra Director Joel Schroter encourages students before final concert of their school year.

School Orchestra Director Joel Schroter encourages students before final concert of their school year.

Gentle, soft-spoken and humble, Chris speaks with passion as his graceful hands constantly finger notes on an invisible instrument. It could be a passage from his violin score with the school orchestra, or something on acoustic guitar, viola, piano, clarinet, electric bass, alto saxophone, drums, recorder – even mandolin – that he also plays.

“I’m willing to try anything out,” he said. He also sings with ‘perfect pitch’ — the rare ability to perfectly produce any given note – without a musical instrument as a reference.

2016 was Joel Schroter’s first year as the school’s orchestra director when he met Hernandez, an incoming freshman at the time. From the first weeks of orchestra class, Schroter knew Hernandez had a musical mind that overflowed with a love and passion for music.

“I could also sense some frustration coming from him — too many musical ideas and not enough musical outlets. When it came to performing on violin, I could tell that he was only frustrated by technical limitations matching the music he was hearing in his head,” Schroter recalled.

“Over the past three years, Chris matured in his ability and technique, and as he develops, he has also been able to explore new musical ideas,” Schroter said.

“Since Chris is a multi-instrumentalist as well as a digital music arranger and producer, I encouraged him to look into composition as a possible path. He can sit at a piano or a guitar and score music for various instruments without having to be an expert performer on those instruments,” Schroter added. The “Ciudadela” composition was one of the results.

If there’s a piano nearby, Chris will find it and begin to play. “The music is in my head,” he explains.

If there’s a piano nearby, Chris will find it and begin to play. “The music is in my head,” he explains.

“I wanted Chris and my students to experience the entire process without much interference from me,” said Schroter, who remained behind the scenes and allowed the creativity and collaboration to be “organic.”

From composition to concert performance, Hernandez was in charge of the composition, class rehearsals, score revisions and concert preparation. Schroter met with his young composer few times to help guide his focus and give him some rehearsal advice, “But once he stepped on the podium, he was in charge of the process,” he said. “This guy doesn’t hold back! And if he is self-conscious, it is very hard to detect. It reminds me of a child on a playground — having a blast, no hesitations, and just being caught up in the moment, enjoying life. When Chris is conducting on the podium, he just goes for it and it looks like he is having the time of his life,” Schroter said.

“I’ve been an orchestra director for 14 years. Sitting in the back of the class and watching Chris work with the chamber orchestra, seeing him light up when he hears his composition being performed by others, it gave me a sense of joy that I cannot put into words,” Schroter added.

The slender musician often paces when concentrating on a composition idea. He has numerous musical phrases collected on his smartphone and a stash of music manuscripts, ideas and musical themes that may one day find a home as part of a larger piece.

His internal music calms him, even during his academic studies. “Whenever there’s a test, the themes help me stay focused and gets me into a certain zone,” he said.

Ricardo Hernandez smiled with his son’s admission. He sang to his son every night for months – before his birth.

“When my wife was pregnant, I would come home very late from work. I didn’t get home until after midnight,” the senior Hernandez recalled. He emigrated with his brother to the U.S. from Mexico City in 1994, and owns an auto mechanic shop in Macon, Georgia.

Chris plays his guitar as family sings Latin favorites at home.

“From the beginning, I laid my head on Sandy’s belly every night and sang to him. They were songs my dad and my mom used to sing. I come from a family where music was just a way of life,” he said.

“I knew our son liked music because I could feel him kick when Ricky sang to him,” Sandra joked.

The musical immersion continued as Chris grew to toddler age. Ricardo and Sandy enrolled their son in music classes at a local Gymboree center. “As a two-year-old he loved to play the maracas and wooden rhythm sticks along with the music. I played my guitar for him at night, sometimes I played recordings of classical piano music like Beethoven, Bach, Mozart and Chopin to help him go to sleep,” Ricardo said.

“Chris was a very quiet child. It was like I didn’t have a child,” Sandy Hernandez remembered. “He was reading at the third-grade level when he was three years old. Chris spent all his time in his room surrounded by his books, sometimes not even wanting to eat dinner. I was worried he may be shy and might get bullied so we tried baseball and soccer for him. That didn’t work, except for swimming — he loves to swim at the YMCA,” she said.

Sandra next found a piano teacher for her son. “He loved it and took lessons for six years,” she said. His piano instruction became the basis for all his other instruments and composing skills. “Every teacher he’s had said Chris has a special gift,” she said.

Chris Hernandez has fond memories of playing duets with his father. “My dad would play guitar and I would play piano,” he said. “The thing I admire about my dad the most is that he can blend in with any situation. He is a jack of all trades.”

When Hernandez turned eight, he wanted to play guitar like his father. “He showed me basic chords, and at first I didn’t really like it because of how hard it seemed. But I learned a lot from watching YouTube tutorials. It is very similar to piano, and once I figured that out I could play okay after a few months,” he said.

As Hernandez entered his middle school’s music program, Sandra Hernandez purchased a saxophone and violin for him. “Mom found them on Craig’s list. She knew I would make a connection to them somehow, “Chris recalled.

He studied both instruments and was soon exploring tunes far beyond the required repertoire. “I would listen to recordings and analyze the chord structure of songs. I picked out the notes. It wasn’t that difficult,” he said.

By high school, Sandy her husband knew their son needed more. “We went into our savings to buy a better violin. I knew music was so important to Chris and it would become his life, so we did everything would could to support him,” she said.

His fellow students universally describe him as energetic, immensely talented and passionate. “Chris has these rhythms and these notes that he just plays, they come out of him like magic,” one fellow student said.

Ricardo Hernandez listens as his son Chris practices passages his guitar in his bedroom.

As Hernandez approaches his senior year in high school, his command of the guitar, violin and his singing voice is well evident. He leads the family as they happily sing Latin favorites together at home.

Once his high school days are behind him in 2019, Hernandez has his eyes on Berklee College of Music in Boston, where he plans to study musical performance and composition.

Chris with supportive parents Sandra and Ricardo Hernandez.

He is undaunted by the school’s nearly $60,000 per year tuition and fees. “With the power of a scholarship and hard work, anything is possible. I know I can do it,” he said.

He is torn between performance and composition. “Therein lies the rub,” he admitted. “The composing part of it is bringing something to life. It may have been influenced by others, but it’s coming from you, you’re the primary creator of it. With performance, you’re playing what someone else has created. Music is always subjective, and you’re putting your interpretation to it,” he said. Though Hernandez loves to compose, his heart leans more toward performance.

“If I had to choose one, I would be playing with the Boston Philharmonic,” Hernandez said. His family plans to have front row seats when that day comes, and perhaps Joel Schroter as well.